Stars in the Dustbin: Sarah Christman’s As Above, So Below

“Memory is an editing process; it’s an unnatural selection.” —from Letter to Bill Gates, by Sarah Christman

“There are some things we let go of very easily and there are some things we have a really, really hard time letting go of. When you mix the two categories it’s going to be a problem.” This statement comes about two-thirds of the way through Brooklyn, NY-based scholar and filmmaker Sarah Christman’s essay film, As Above, So Below (2012). It is made by the “Anthropologist in Residence” for the New York Department of Sanitation, in voiceover, while still landscape shots show the city park that covers the vast site in New York’s Staten Island that until recently housed the Fresh Kills Landfill. In its time, it was the largest landfill (and in fact, at one point, largest man-made structure) in the world. If you were in New York City any time in the years between 1950 and 2000, chances are whatever trash you discarded is sitting right there, now covered up by grass, concrete, and young trees. It will remain there for a very long time.

What the Anthropologist in Residence for the New York Department of Sanitation was referring to in the above quote, specifically, was the fact that the last things to be dumped into the Fresh Kills Landfill, after the site had been technically closed, was tons of wreckage from the attack of the World Trade Center of September 11. But the statement sews together the various ideas in As Above, So Below together so pointedly, it’s disarming, a punch that resonates through the rest of the film. The apt comparison of the ephemerality of being and the technology of the unwanted has a way of digging up all sorts of memory corpses.

***

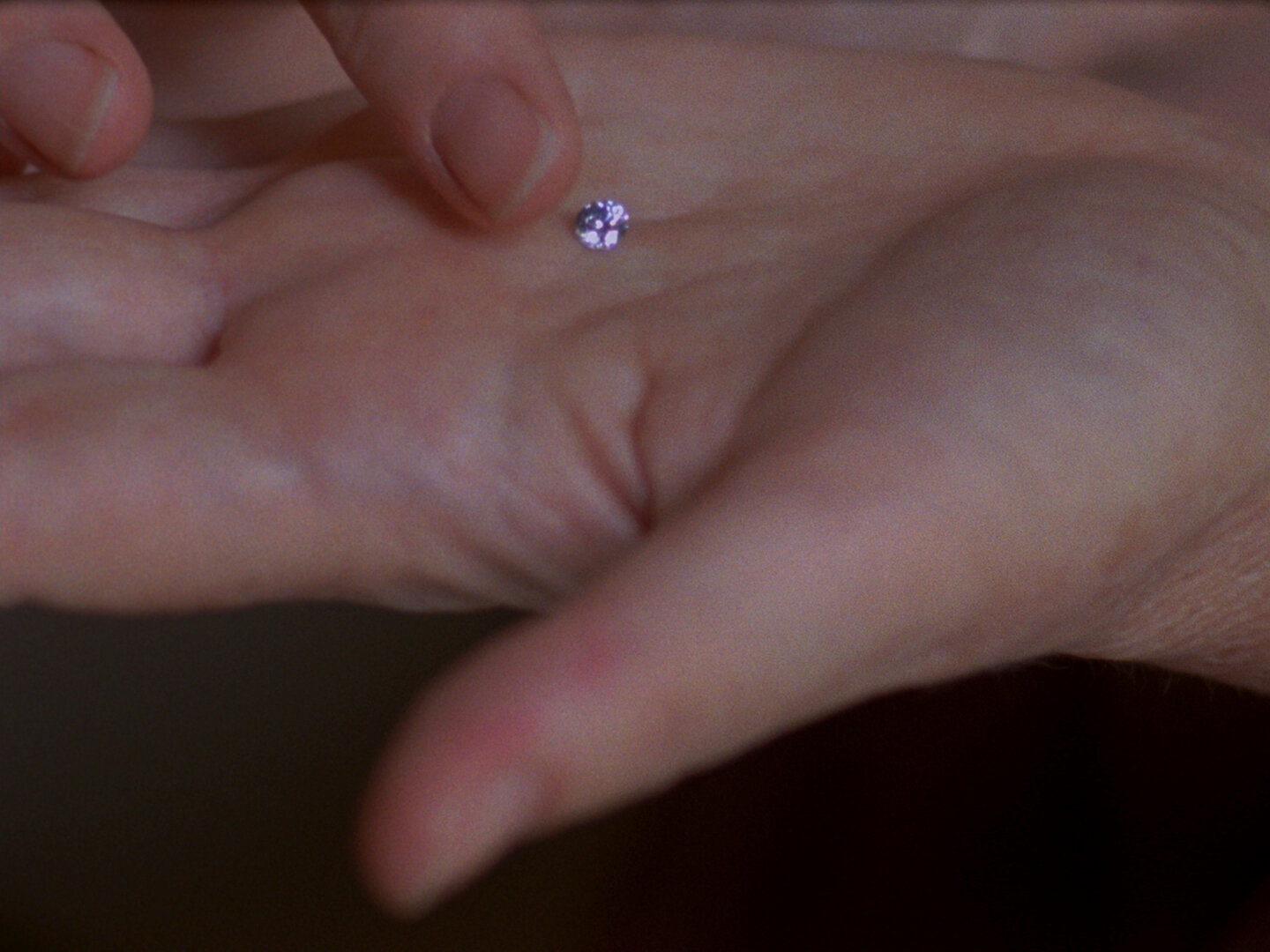

Prior to the scene at Fresh Kills, we see Sarah and her mother in her mother’s apartment, researching and discussing a plan to turn Sarah’s dead stepfather, Steve, into a memorial diamond--a relatively new innovation where the ashes of human (or potentially animal, or plant) remains undergo a strong enough degree of pressure to transform them into a tiny jewel. The gem can then accompany the bereaved, adorn them, remind them of their lost loved one. It turns the symbolic matter of the dead into a new, rarefied, aestheticized object--one more elegant, able to be loaded with more meaning and projection than the urn, or the gravestone. An object-sublimation of an idea of the thing remaining of one’s remains.

In another scene lasting several slow-burning minutes, Sarah’s mother’s extensive chronology of the stages of her husband’s fatal sickness plays over a series of still shots of ice melting from trees, mixed with enormous piles of garbage in garbage bags left out on the streets of Brooklyn after a blizzard. Plastic bottles with residual liquids in them, take-out containers, furniture chards--all peeking out of the dirty snow. The monologue and image are a perplexing and confusing montage. Snow, garbage, cancer, water, memory, icicles, and trees.

What you want to remember you remember, what you want to keep you keep, but what you don’t want to remember is all mixed up in objects. In one of those unexpected consequences of progress, consumerism and the individuality expressed through it hamper the ability to recover from loss. A memorable passage from one of the most intellectually therapeutic books on grief of recent years, Joan Didion’s In The Year of Magical Thinking, involves the author’s struggle with the fact of her dead husband’s shoes left sitting out. The shoes remain, so he will come back to fill them, logic states. The pile of shoes in the proverbial closet are another ordeal--what/which to keep and for how long. The more things there are the more meaning the seemingly meaningless can hold. The smell of a sweater dissipates, but the object stays intact long enough to outlive you if you let it. And there are so many things connected to every human, with all sorts of imputed freight. So many of the less weighted things get discarded. The half-used stack of post-it notes, or the chewed pencil. In the garbage the memories of the living and things of the dead mingle, along with an inordinate amount of other products people would much sooner forget were ever in their hands, houses, sights, minds. Little consumer mistakes. Impulse buys.

Later on, again in voice-over, Christman’s mother tells the story about how, soon after Steve’s death, a Hawk landed in her backyard and stayed there for a long time. Her son, she tells us, encouraged her suspicions about the meaning of the unusual visitor: “That’s Steve... He’s not gonna leave you that easily.” This immediately called to mind a monologue on the radio show This American Life, where Kathy Russo shares that after the death of her husband, the troubled actor Spalding Gray, she and each of her children were visited by a bird--possibly the same bird--that appeared to them to have a message to pass on... Which is to say, it’s one of those types of stories people corroborate after a mutual loved one dies. But which object is he--a bird, a diamond, a piece of Kleenex ordered online just before he took his last breath, or his photograph, his shoes? Is he; are they, in the garbage, too?

Previous to making this hour-long film, Christman composed a series of shorter experimental films. Her 2007 short Letter to Bill Gates, is something of a prelude to As Above, So Below, in terms of the connections it makes. Several disparate nodes including: a Pennsylvania mining town that has been burning uncontrollably for decades; the compound kept by Bill Gates (called Iron Mountain), of millions of images from his image-owning company, Corbis; and the lengthy personal data traces left from an internet search, are deployed to create an exploration of contemporary impermanence and indelibility. As an artist who works with actual film stock, she’s keenly attuned to a certain kind of object-longing and loss. Film is a chemical reaction that destroys itself organically, eventually. The archive can only conserve and preserve so much. Folding elements into images that build into ideas makes a stab at perpetuity, but then there’s the market--the life of a film, the idea-commodity, the marginalization of working in the world of ideas. The market allows this born-dying creation to be seen by hundreds, maybe thousands over a year, and then it’s largely forgotten, even if it is “available” in some digital form, it lies underneath an immense, insurmountable pile of increasingly new data. More movies, other topics, counter-stimulation. It doesn’t even get the dignity of dying.

***

When we first meet the voice of the Anthropologist in Residence for the New York City Department of Sanitation in As Above, So Below, she’s narrating at the site of Dead Horse Bay, an iconic landmark of the city’s early history of processing its untenable loads of waste, and a demonstration of its early class relations. From the 1850s until the last residents were evicted in 1936, the beach housed a community built on discards. During WWI, it took in all of the household garbage of New York and the daily remains of all five borough’s animal dead, and processed it all into glycerin, fertilizer, and glue. In 1936, the island’s cottages were bulldozed and all the remaining inhabitants were forced out. Their object-remains were buried, but, because of erosion, they now continually litter the Bay with waste, which in turn washes back ashore. The sand functions like the snow covering up garbage on the street, or a suspect park sprouting up over a natural tragedy. It’s nice to imagine that all the forgotten, or all the lost, or all the discarded things could be instead compacted into tiny gems--squished into something tiny, sharp, reflective, and rare. Memories following suit.